Third Anglo-Burmese War

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (November 2011) |

| Third Anglo-Burmese War တတိယအင်္ဂလိပ်-မြန်မာစစ် | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Anglo-Burmese Wars | |||||||

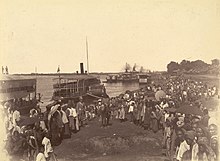

The nominal surrender of the Burmese Army, 27 November 1885, at Ava. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

The Third Anglo-Burmese War (Burmese: တတိယအင်္ဂလိပ်–မြန်မာစစ်, romanized: Tatiya Ingaleik–Myanma Sit), also known as the Third Burma War, took place during 7–29 November 1885, with sporadic resistance continuing into 1887. It was the final of three wars fought in the 19th century between the Burmese and the British. The war saw the loss of sovereignty of an independent Burma under the Konbaung dynasty, whose rule had already been reduced to the territory known as Upper Burma, the region of Lower Burma having been annexed by the British in 1853, following the Second Anglo-Burmese War.

Following the war, Burma came under the rule of the British Raj as one of its provinces. From 1937, the British governed Burma as a separate colony until Burma achieved independence as a republic in 1948.

Background

[edit]

Following a succession crisis in Burma in 1878, the British Resident in Burma was withdrawn, ending official diplomatic relations between the countries. The British considered a new war in response but other ongoing wars in Africa and Afghanistan led them to reject a war at that time.

During the 1880s, the British became concerned about contacts between Burma and France. Wars in Indochina had brought the French to the borders of Burma. In May 1883, a high-level Burmese delegation left for Europe. Officially it was to gather industrial knowledge, but it soon made its way to Paris where it began negotiations with the French Foreign Minister Jules Ferry. Ferry eventually admitted to the British ambassador that the Burmese were attempting to negotiate a political alliance along with a purchase of military equipment. The British were troubled by the Burmese action and relations worsened between the two countries.

During the discussions between the French and Burmese in Paris, a boundary dispute on the frontier of India and Burma broke out. In 1881, the British authorities in India appointed a commission to unilaterally mark out the border between the two countries. In the course of its work, the commission began demanding the Burmese authorities in villages determined by the British to be on their side of the line should withdraw. The Burmese objected continuously, but eventually backed down.

In 1885, the French consul M. Hass moved to Mandalay. He negotiated the establishment of a French Bank in Burma, a concession for a railway from Mandalay to the northern border of British Burma and a French role in running monopolies controlled by the Burmese government. The British reacted with diplomatic force and convinced the French government to recall Haas who was removed allegedly "for reasons of health". While the French had backed down in Burma, the French actions as well as many other events convinced the British to take action against Burma.

A fine was imposed on the Bombay Burmah Trading Corporation for under-reporting its extractions of teak from Toungoo and not paying its employees. The company was fined by a Burmese court, and some of its timber was seized by the Burmese officials. The company and the British government claimed the charges were false and the Burmese courts were corrupt. The British demanded the Burmese government accept a British-appointed arbitrator to settle the dispute. When the Burmese refused, the British issued an ultimatum on 22 October 1885. The ultimatum demanded that the Burmese accept a new British resident in Mandalay, that any legal action or fines against the company be suspended until the arrival of the resident, that Burma submit to British control of its foreign relations and that Burma should provide the British with commercial facilities for the development of trade between northern Burma and China.

The acceptance of the ultimatum would have ended any real Burmese independence and reduced the country to something similar to the semi-independent princely states of British India. By 9 November, a practical refusal of the terms having been received at Rangoon, the occupation of Mandalay and the dethronement of the Burmese king Thibaw Min were decided upon.[1] The annexation of the Burmese kingdom had probably also been decided.

War

[edit]

At this time the country was one of dense jungle, and was therefore unfavourable for military operations, the British knew little of the interior of Upper Burma; but British steamers had for years been running on the great river highway of the Irrawaddy River, from Rangoon to Mandalay, and it was obvious that the quickest and most satisfactory method of carrying out the British campaign was an advance by water direct on the capital. Further, a large number of light-draught river steamers and barges (or flats), belonging to the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company under the control of Frederick Charles Kennedy,[2] were available at Rangoon, and the local knowledge of the company's officers of the difficult river navigation was at the disposal of the British forces.[1]

Major-General, afterwards Sir, Harry Prendergast was placed in command of the invasion. As was only to be expected in an enterprise of this description, the navy as well as the army was called in requisition; and as usual the services rendered by the seamen and guns were most important. The total effective force available was 3,029 British troops, 6,005 Indian sepoys and 67 guns, and for river service, 24 machine guns.[3] The river fleet which conveyed the troops and stores was composed of more than 55 steamers, barges, and launches among other things.[1]

Thayetmyo was the British post on the river nearest to the frontier, and here, by 14 November, five days after Thibaw's answer had been received, practically the whole expedition was assembled. On the same day General Prendergast received instructions to commence operations. The Burmese king and his country were taken completely by surprise by the rapidity of the advance. There had been no time for them to collect and organize any resistance. They had not even been able to block the river by sinking steamers, etc., across it, for, on the very day of the receipt of orders to advance, the armed steamers, the Irrawaddy and the Kathleen, engaged the nearest Burmese batteries, and brought out from under their guns the Burmese King's steamer and some barges which were lying in readiness for this very purpose. On the 16th the batteries themselves on both banks were taken by a land attack, the Burmese being evidently unprepared and making no resistance. On 17 November, however, at Minhla, on the right bank of the river, the Burmese in considerable force held successively a barricade, a pagoda and the redoubt of Minhla. The attack was pressed home by a brigade of British Indian infantry on shore, covered by a bombardment from the river, and the Burmese were defeated with a loss of 170 killed and 276 prisoners, besides many more drowned in the attempt to escape by river. The advance was continued next day and the following days, the naval brigade and heavy artillery leading and silencing in succession the Burmese river defences at Nyaung-U, Pakokku and Myingyan.[1]

However, some sources[who?] say that the Burmese resistance was not fierce because the defence minister of Thibaw, Kinwun Mingyi U Kaung, who wanted to negotiate peace with the British, issued an order to the Burmese troops not to attack the British. His order was obeyed by some, but not all Burmese brigades. In addition, the British passed out propaganda while marching through Burma, insisting to the Burmese that they did not intend to occupy the country so much as depose the king Thibaw and enthrone Prince Nyaungyan (an elder half-brother of Thibaw) as the new king.[4] At that time, most of the Burmese did not like Thibaw both because of the poor management of his government and because he and/or his king-makers had executed nearly a hundred royal princes and princesses when he ascended the throne in 1878. Nyaungyan was a survivor of this royal massacre and had been living in exile in British India, although in fact he was already dead by this time. However, the British concealed this fact, and according to some sources[citation needed] the British even brought a man impersonating Prince Nyaungyan along with them on their way to Mandalay so that the Burmese would believe their story of installing a new king. Thus, the Burmese who welcomed this purported new king made no attempt to resist the British forces. However, when it became obvious that the British had actually failed to install a new king and Burma in fact had become annexed to the Raj, fierce rebellions by various Burmese groups, including the troops of the former royal Burmese army, ensued for more than a decade. U Kaung's role in the initial collapse of Burmese resistance later gave rise to the popular mnemonic U Kaung lein htouk, minzet pyouk ("U Kaung's treachery, end of dynasty": U (ဥ) =1, Ka (က) =2, La (လ) =4, Hta (ထ) =7 in Burmese numerology i.e. Burmese Era 1247 or 1885AD).

On 26 November, when the flotilla was approaching the capital Ava, envoys from King Thibaw met General Prendergast with offers of surrender; and on the 27th, when the ships were lying off that city and ready to commence hostilities, the order from the king to his troops to lay down their arms was received. There were three strong forts here, full at that moment with thousands of armed Burmese, and though a large number of these filed past and laid down their arms by the king's command, still many more were allowed to disperse with their weapons; and these, in the time that followed, broke up into guerrilla bands and prolonged the war for years. Meanwhile, however, the surrender of the king of Burma was complete; and on 28 November, in less than a fortnight from the declaration of war, Mandalay had fallen, and King Thibaw was taken prisoner, and every strong fort and town on the river, and all the king's ordnance (1861 pieces), and thousands of rifles, muskets and arms had been taken, primarily from the Mandalay palace and the city itself.[1] The proceeds were sold off at a profit of 9 lakhs of rupees (roughly 60,000 pound sterling).

From Mandalay, General Prendergast reached Bhamo on 28 December. This was a very important move, as it forestalled the Chinese, who had their own claims and border disputes with Burma. Though the king was dethroned and exiled with the royal family to India, and the capital and the whole of the river in the hands of the British, bands of insurgents took advantage of the situation to continue an anti-social resistance which proved very difficult to defeat.[1]

Annexation and resistance

[edit]

Burma was annexed by the British on January 1, 1886,[5] by the proclamation of the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, Lord Dufferin.

PROCLAMATION.

By command of the Queen-Empress, it is hereby notified that the territories formerly governed by King Theebaw, will no longer be under his rule, but have become part of Her Majesty's dominions, and will during Her Majesty's pleasure, be administered by such Officers as the Viceroy and Governor-General may from time to time appoint.

The 1st January 1886.

DUFFERIN,

Viceroy and Governor-General.

The annexation sparked an anti-colonial resistance which would last until 1896.[4] The final, and now completely successful, conquest of the country, under the direction of Sir Frederick (later Earl) Roberts, was only brought about by an extensive system of small military police protective posts scattered all over the country, and small lightly equipped columns moving out in response whenever a gathering of freedom fighters occurred. The British poured reinforcements into the country, and it was in this phase of the campaign, lasting several years that the most difficult and brutal work of repression fell to the lot of the remaining British and Indian troops.[1] Ultimately, despite the efforts of Roberts, the freedom fighters in Burma would remain active for another decade.[4]

The British also extended their control into the tribal areas of the Kachin Hills and Chin Hills. These territories, only nominally ruled even by the Burmese kingdom, were grabbed by the British. Also grabbed were disputed territories in northern Burma claimed by the Qing government.[4]

No account of the Third Burmese War would be complete without a reference to the first (and perhaps for this reason, the most notable) land advance into the country. This was carried out in November 1885 from Toungoo, the British frontier post in the east of the country. A small column of all arms carried it out under Colonel W. P. Dicken, 3rd Madras Light Infantry, the first objective being Ningyan (Pyinmana). The suppression of freedom fighters was completely successful, in spite of a good deal of scattered resistance, and the force afterwards moved forward to Yamethin and Hlaingdet. As inland operations developed, the lack of mounted troops was badly felt, and several regiments of cavalry were brought over from India, while mounted infantry was raised locally. The British found that without mounted troops it was generally impossible to fight the Burmese successfully.[1]

Prize Committee

[edit]

Following the annexation of Burma, valuable possessions of the Burmese Government were stolen by the British authorities[citation needed]. Many items that could be easily transported such as gold, jewellery, silk and ornamental objects were shipped back to Britain and presented as gifts to the royal family and notables of Britain,[4] others were auctioned.[6] An organisation, the "Prize Committee, Mandalay", was instituted to dispose of the possessions of the former Burmese government.[6] The majority of auctioned items were sold to Army and Navy officers and civil servants as well as the occasional European traveller.

Items made of valuable metals which were damaged or deemed to be of little artistic value were melted down for bullion. Articles deemed to be of very high value were shipped to the Executive Engineer in Calcutta.[7] Some items of high religious importance, including 11 gold idols of Lord Buddha, were retained by the Calcutta museum to be restored and if later requested returned to descendants of Burmese royalty. Machinery, steamers and items of practical value were usually transferred to the British government or purchased at well below market value.[7] Ordnance including cast-iron guns, cannons and field guns were for the most part destroyed or disposed of in deep water.

In 1886, a military expedition was launched to "open up" the lucrative ruby mines at Mogok and make them available to British merchants. George Skelton Streeter, a gem expert and son of Edmund Streeter of the Streeters & Co Ltd jewellery company in London, accompanied the expedition and stayed there to work as a government valuer in the British-run mines.[8]

See also

[edit]- History of Burma

- Konbaung dynasty

- First Anglo-Burmese War (1824–1826)

- Second Anglo-Burmese War (1852–1853)

- British rule in Burma

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Burmese Wars s.v. Third Burmese War, 1885-86". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 847–848.

- ^ "Lot 21, Orders, Decorations, Medals and Militaria. To coin... (19 September 2003) | Dix Noonan Webb". Archived from the original on 11 December 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ^ The Victorians at war, 1815-1914: an encyclopedia of British military history. p. 70.

- ^ a b c d e Thant, Myint-U (2000). The Making of Modern Burma. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-521-78021-7.

- ^ Hays, Jeffrey. "BRITISH RULE OF BURMA | Facts and Details". factsanddetails.com. Archived from the original on 17 June 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ a b Kyan, Daw (1979). The Prizes of War. Historical Research Department, Washington University. pp. 1–3.

- ^ a b Kyan, Daw (1979). The Prizes of War. Historical Research Department, Washington University. p. 5.

- ^ "Edmund Streeter [of the Streeters & Co Ltd jewellery company in London] was a scholar and an author, and a considerable authority on precious stones. The firm's catalogue was more than simply a commercial presentation, it was also an introduction to the infant science of Gemology. Streeter and his family were ruthless robbers of colonial assets in the true Victorian mould. His son George Skelton Streeter accompanied a military expedition to open up the Burmese ruby mines at Mogok in 1886, and stayed there to work as a government valuer. His eldest son Harry lost his life in Australian waters while pearling with the company fleet". Peter Hinks, Introduction to "Victorian Jewellery", Studio Editions, London 1991.

Prendergast, H.D.V. (2016). 'Memorials and trophies' - cannon in Britain from the Third Anglo-Burmese War. Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research 94, pp. 106-128.

Further reading

[edit]- Charney, Michael W. Powerful Learning: Buddhist Literati and the Throne in Burma's Last Dynasty, 1752–1885. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan. 2006.

- Hall, D. G. E. Europe and Burma (Oxford University Press, 1945)

- Martin D. W. Jones, 'The War of Lost Footsteps. A Re-assessment of the Third Burmese War, 1885–1896', Bulletin of the Military Historical Society, xxxx (no.157), August 1989, pp. 36–40

- Third Anglo-Burmese War: How to Stop a War... Burmese War page at OnWar.com (archived 22 November 2005)

External links

[edit]- Third Anglo-Burmese War British regiments

- The Somerset Light Infantry in the Third Burmese War

- The 2nd Battalion Queen's (Royal West Surrey) Regiment

- Burma: The Third War Stephen Luscombe (photos)

- Group of Gen. Prendergast[dead link] photo at Mandalay Palace